Synopsis

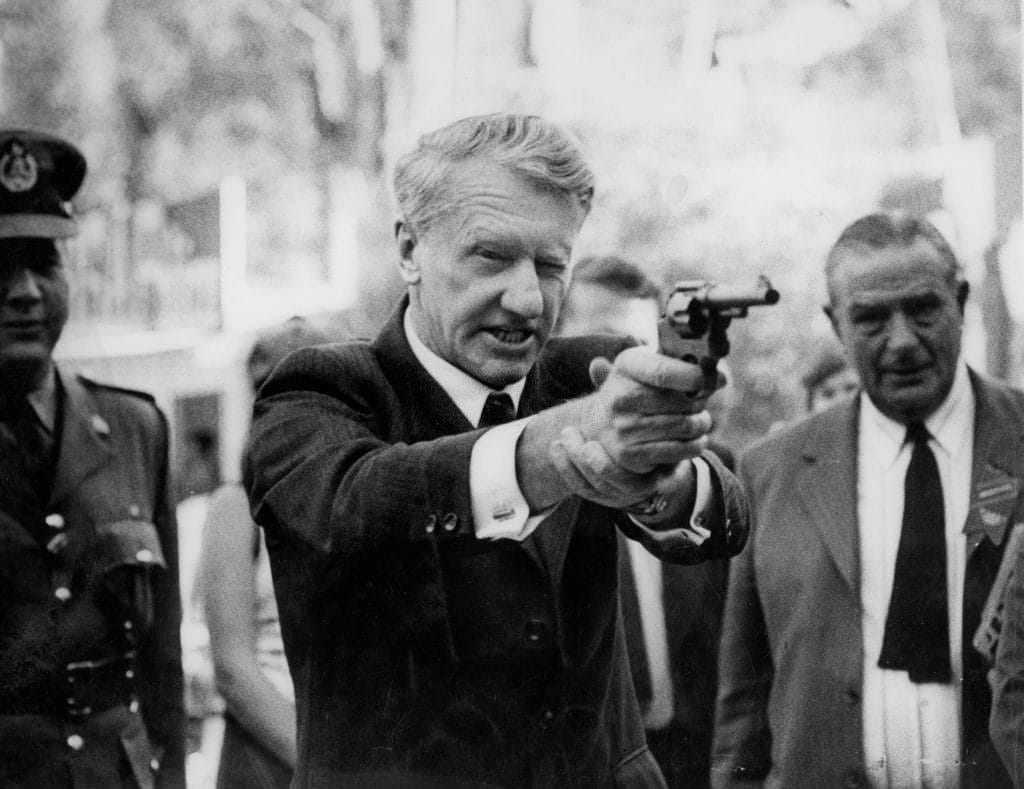

Ever since his unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) from Britain in November 1965, Rhodesian Premier Ian Smith has tried to maintain what he called “acceptable standards of civilisation” – the preservation of white supremacy and the denial of African majority rule. As the Geneva conference on a final Rhodesian settlement gets underway, ITN’s Roving Report report looks back at the career of this tough, uncompromising politician.

Early Life

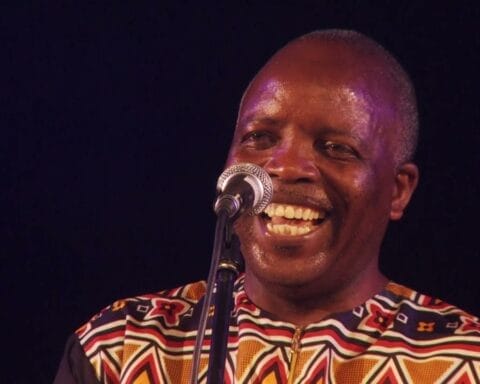

Ian Douglas Smith, was the first native-born prime minister of the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, and the last white Prime Minister before independence. He was also an ardent advocate of white minority rule.

Smith was born on April 8, 1919, in Selukwe, Southern Rhodesia. He attended Selukwe High School where he was an average student, who was outstanding in sports. His studies at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa, were interrupted to join the Royal Air Force as a fighter pilot in World War II. Smith later returned to Rhodes University, where he earned the bachelor of commerce degree.

After University he returned to his Selukwe farm and married Janet Watt (they had two sons and a daughter).

Political career

Smith was elected to the Southern Rhodesian Assembly in 1948.

He joined the governing Federal Party when the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was formed in 1953. By 1958 Smith had become chief government whip in Parliament, but when the Federalists supported a new constitution allowing greater representation for black Africans in Parliament, Smith founded the Rhodesian Front (1961) and attracted white-supremacist support. Promising independence from Britain with a government based upon the white minority, his party won a surprise victory in the election of 1962.

Smith rose to power because of his strong white supremacist views at a time when African countries to the north were gaining independence under black rule. At the same time Britain was pressing for constitutional changes enabling unimpeded progress toward African majority rule. Smith represented 240,000 whites determined to control a country in which 4.5 million Africans also lived.

Smith’s goal was to negotiate independence for Rhodesia but British prime minister Harold Wilson would not agree without guarantees of unimpeded African progress toward majority rule. Frequent talks in London and Salisbury did not resolve the impasse.

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence

Further negotiations with Britain proved futile, and on Nov. 11, 1965, Smith unilaterally declared Rhodesia’s independence (referred to as the Unilateral Declaration of Independence, or UDI). Great Britain refused to accept Rhodesian independence and retaliated by cutting off Rhodesia from the sterling trade area, dismissing the Smith government, invalidating Rhodesian passports, and banning purchases of Rhodesia’s cash crop of tobacco. Prime Minister Wilson declared that he would not use force to bring Rhodesia to heel.