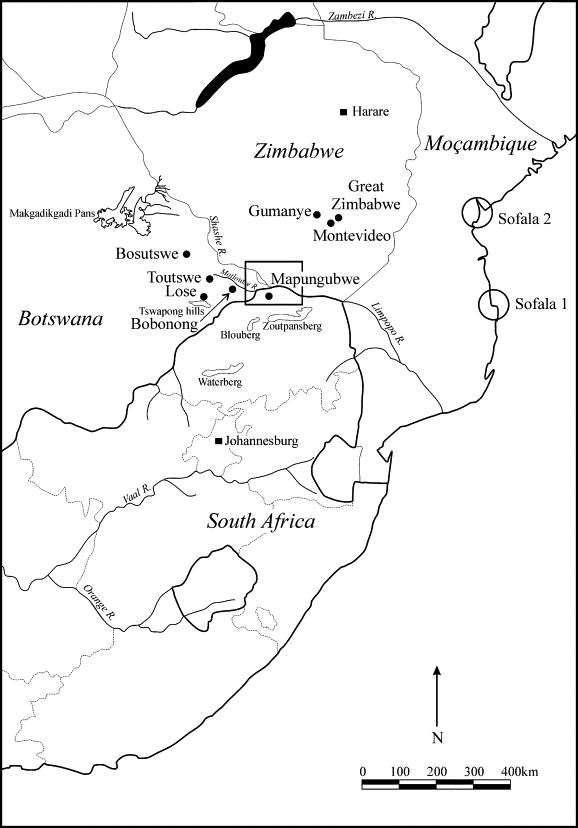

The ancient city of Mapungubwe (meaning ‘hill of the jackal’) is an Iron Age archaeological site in the Limpopo Province on the border between South Africa, Zimbabwe and Botswana. It sits close to the point where the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers meet.

One thousand years ago, Mapungubwe appears to have been the centre of the largest known kingdom in the African sub-continent before it was abandoned in the 14th century.

The Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape demonstrates the rise and fall of the first indigenous kingdom in Southern Africa between 900 and 1,300 AD. The core area covers nearly 30,000 ha and is supported by a suggested buffer zone of around 100,000 ha. Within the collectively known Zhizo sites are the remains of three capitals – Schroda; Leopard’s Kopje; and the final one located around Mapungubwe hill – and their satellite settlements and lands around the confluence of the Limpopo and the Shashe rivers whose fertility supported a large population within the kingdom.

The Mapungubwe Artifacts

The Mapungubwe Collection curated by at the University of Pretoria Museums comprises archaeological material excavated at the Mapungubwe. The archaeological collection comprises ceramics, metals, trade glass beads, indigenous beads, clay figurines, and bone and ivory artifacts.

Mapungubwe’s position at the crossing of the north/south and east/west routes in southern Africa also enabled it to control trade, through the East African ports to India and China, and throughout southern Africa. From its hinterland it harvested gold and ivory – commodities in scarce supply elsewhere – and this brought it great wealth as displayed through imports such as Chinese porcelain and Persian glass beads.

This international trade also created a society that was closely linked to ideological adjustments, and changes in architecture and settlement planning. Until its demise at the end of the 13th century AD, Mapungubwe was the most important inland settlement in the African subcontinent and the cultural landscape contains a wealth of information in archaeological sites that records its development. The evidence reveals how trade increased and developed in a pattern influenced by an elite class with a sacred leadership where the king was secluded from the commoners located in the surrounding settlements.

Mapungubwe’s demise was brought about by climatic change. During its final two millennia, periods of warmer and wetter conditions suitable for agriculture in the Limpopo/Shashe valley were interspersed with cooler and drier pulses. When rainfall decreased after 1300 AD, the land could no longer sustain a high population using traditional farming methods, and the inhabitants were obliged to disperse. Mapungubwe’s position as a power base shifted north to Great Zimbabwe and, later, Khami.

The remains of this famous kingdom, when viewed against the present day fauna and flora, and the geo-morphological formations of the Limpopo/Shashe confluence, create an impressive cultural landscape of universal significance.